“Forming these ridges brings water closer to the surface, and that increases the chance that you'll have an opportunity for exchange to get those chemicals into the water,” Schroeder says. These chemicals reach the surface of the ice shell, which blocks the chemicals from reaching the liquid water below, Schroeder says. If combined with water, chemicals from space and nearby moons like Io could make Europa habitable. But the ocean is separated from the surface by the thick ice shell.

Underneath Europa’s ice shell lies a global ocean, and evidence suggests it has more liquid water than the Earth. “If the same process covers the formation of the double ridges on Europa, then there would be pockets of water underneath these ridges all over Europa,” Schroeder says, “suggesting that water may be much more abundant in the middle of the ice shelf than we would have thought.” In Greenland, the ridges were formed by refrozen pockets of water, he says. His research group, which studies both Europa and Earth’s ice sheets using radar, discovered similar features on the surface of Greenland. The surface of Europa, some 390 million miles away, shows “striking double ridge features” that are symmetric on both sides, with a trough in the middle, says Stanford University geophysics professor Dustin Schroeder. Scientists say similarities between Greenland and Europa show Jupiter's moon might be able to sustain life. (NASA/AFP via Getty Images) This article is more than 1 year old.

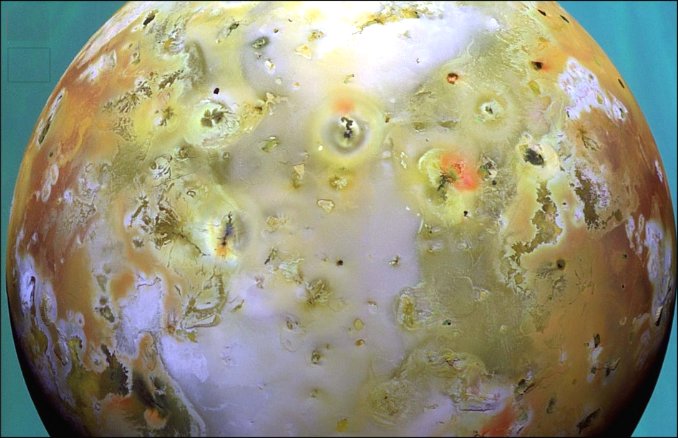

From left to right, the moons shown are Io, Europa, Ganymede and Callisto. This NASA file composite image shows the Jovian system, including the edge of Jupiter with its Great Red Spot, and Jupiter's four largest moons, known as the Galilean satellites.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)